“The entire sculpture can fit on a flash drive.”

Frank Benson gave a

lecture as part of the Leonard Hare Memorial Lecture Series at the University

of Bristol. The Lectureship was established in 1946 in memory of George Hare

Leonard, Professor of Modern History. Each year, a lecture is presented on fine

arts. Benson discussed his practice as well as his sculpture, Castaway, which has recently been installed in Bristol’s

Goldney Gardens.

|

| Castaway (2019) (Photo: Ruby Salter) |

Now on display in the expansive gardens of Goldney Hall, Bristol, is a life size bronze statue of Alexander Selkirk, the 18th century mariner who was allegedly the inspiration for Robinson Crusoe. Castaway depicts the mariner in a crouching position, eyes locked on a point ahead. The ship that eventually rescued Selkirk was funded by the Goldney family. As the title of the sculpture suggests, Benson imagines how a seaman may look if he had washed up ashore on a deserted island. Far from a simple portrait of Selkirk, the sculpture is more a representation of the fictional archetype of a ‘castaway’, the same figure portrayed by Tom Hanks in Cast Away or Matt Damon in The Martian. Benson’s depiction, topped with a strange shell-like hat and accompanied by a plastic detergent bottle, seems curious at first. Yet, as Benson outlined in his lecture, the sculpture is an amalgamation of ideas he has pursued throughout his artistic career.

|

| The Martian |

|

| Melted Beer Pitcher (2002) |

Photography was Benson’s initial exploration into experimental

art. The first artwork he shows in the lecture is a photograph of a melted beer

pitcher (2002). Benson talks passionately about the transformation that occurred

when he placed a plastic pitcher in a microwave. The ‘found object’ underwent a

metamorphosis, into another, unrecognisable object. He talks about how

interested he is in the medium of photographing his sculptures. The very act of

translating a 3D object into a 2D rendering changes how we understand it, there

is an extra level of ambiguity, the object becomes far more mysterious.

|

| Chocolate Fountain (2008) |

|

| Meret Oppenheim, Breakfust in Fur, 1936 |

His MDF Piece (2008) is equally as engaging.

Here, Benson replicates the motion of a piece of paper falling to the floor, humorously

rendered using heavy, dense wood. Like the artwork of Claes Oldenburg, Benson’s

art is at once impractical, intriguing and witty.

|

| MDF Piece, (2008) |

|

| Claes Oldenburg, Giant Soft Fan (1966) |

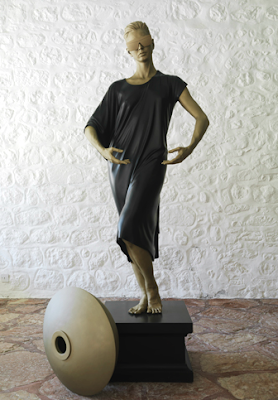

Although Benson’s sculptures of people may seem to be of a

different genre of art, they still engage with this fascination with material

and transforming objects. A homage to street performers, Human Statue (2005) depicts a nude in silver paint. It is incredibly

life like, helped by medical-grade glass eyes, and is often mistaken by gallery-goers

as live performance art, rather than sculpture.

|

| Human Statue (2005) |

For his Human Statue

(Jesse), Benson produced a 3D scan and print of the model. He uses a digital

sculpting programme called Z-Brush. It is often used in sci-fi films and video

games, which makes Benson’s sculptures a captivating blend of industrial

design, fine arts and special effects. The method allows him to create numerous

versions of the sculpture, and in 2011, he created a version with a stone

dress. The stone was sourced from a quarry in Carrara, Italy, which has been carving

stone into sculpture for centuries. It is now done using robots, a fascinating

interplay of ancient and contemporary techniques and resources.

|

| Human Statue (Jesse), 2008 |

Benson jokes that ‘the entire sculpture can fit on a flash-drive’.

Although it is an off-the-cuff remark, it is an intriguing thought, as this

really may represent the future for sculpting. Benson later tells me how,

because he now has his sculptures saved in a 3D virtual format, the possibilities

are endless, and he is in discussions with an AR (Augmented Reality) software

producer about including his sculptures in a game. This really seems to be the

ultimate metamorphosis: from one object into countless digital variations.

No other sculpture deals with the interplay of technology

and art as beautifully as Juliana (2015).

Rendered in flawless plastic and covered in oily, iridescent blue automotive

paint, the piece seems otherworldly. Benson later mentions that Jeff Koons owns

a version of Juliana and it isn’t

hard to see why. The beautiful play of texture and material, and pushing the

boundaries of technology and art is reminiscent of many of Koons’ sculptures.

But really, Juliana, a video game character come to life, would surely put some

balloon dogs to shame.

Benson’s three figurative sculptures are currently on

display in Oslo, and are undoubtedly captivating in person.

|

| Juliana, (2015) |

Castaway seems to

be the ultimate conclusion to Benson’s career of ideas (so far). Much like many

of his earlier works inspired by ready-made or found pieces, Benson repurposes

a horseshoe crab shell as the castaway’s hat. He says the shells would often

wash up on shore during his childhood, and seem like alien creatures. Likewise,

Tide detergent bottle swould also appear on beaches. Benson says he chose to

use these items as the castaway’s hat and canteen, because he likes the idea

that he would ‘repurpose found objects as a means of survival.’ Benson notes this

is analogous with his position as an artist, finding objects, techniques and ideas

to breathe new life into. The model himself, Joe, reflects the same mindset, posing

in his own clothes, all sourced from thrift stores. Benson comments on his ‘scavenger-mentality’

and ‘resourcefulness’, creating an amazing outfit from found elements, making

him the perfect castaway.

At a time when we search for ways to better reuse and

recycle, whilst also pursuing ever more advanced technology, Benson’s works are

entirely of the moment. Whilst being humorous, beautiful and accessible, they

also comment on where we are as a species. Somewhere in the greenery of Goldney

Gardens sits a bearded man, looking out from under a crab shell, at Bristol’s

coast and wondering what might wash up next.